We know that lumber needs to be dried before using it in construction, and most of us know to ask for kiln dried lumber.

We know that lumber needs to be dried before using it in construction, and most of us know to ask for kiln dried lumber.

(We do know that right? Please say yes)

But did you know that not all kiln dried lumber is equal? Depending on where the lumber comes from, the moisture content of your kiln dried material may not be what you think it is.

6-8% is the accepted moisture content of kiln dried lumber here in North America. But over in Europe where the climate is wetter, 12-15% is the normal kiln dried range. This may not seem like a huge difference, especially if you plan to use the lumber for an exterior application and since its moisture content will rise to match the local climate. However, when working in an arid climate or doing any interior work where climate control is a given, this 4-7% moisture content difference could be disastrous.

“But I’m in North America, why do I care how Europe is drying their lumber??”

– Friendly Neighborhood Grumpy Carpenter

That’s a good question, Mister Grumpy. When we are talking about exotic lumber coming from somewhere abroad, most mills are drying to European standards. In fact, many of these mills are run by European companies. (See a history book, look under “Age of Imperialism”). I’m speaking mostly of European and African species like French Oak, Sapele, Utile, Wenge, African Mahogany, European Beech and others. When this lumber arrives on our shores, it is not as dry as you think it is. It is for this reason that we re-dry the material down to North American standards. But it is not quite as simple as just sticking it in a kiln when it arrives at our yard.

Quality Control is Important

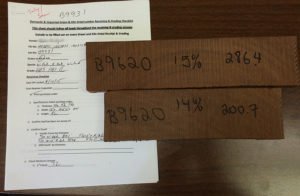

Once we have at least 3 readings in each location within the pack, these numbers are documented on a check-in sheet, and the lumber is then sent through our Vision Tally System to get an accurate board footage and tally; then the lumber is off to our air drying yards so that it can start to acclimate to the local environment here at our East coast yard.

Regardless of the numbers on the lumber, everything ends up in the air dry yard. This is a very important step in the process. The moisture numbers of newly arrived lumber can be suspect, because the inside of shipping containers is a nasty environment any time of the year, and that is bound to affect the lumber’s moisture levels. Letting the lumber sit stacked on blocks and stickered for air flow for a few weeks gives us a more accurate and consistent moisture percentage for the entire pack. It also will dry the lumber further, since our climate is drier than the lumber’s origin. The time a pack of lumber spends in the air dry yard depends on the species and what the final determination is on the moisture content. Rushing lumber into a kiln can be the worst thing you can do, and that can cause all kinds of problems farther down the road.

Stability from Drying

Kiln drying lumber hardens the cell walls in the wood (think about the difference between bread and toast) and will make it more stable in use. While the difference from European standard to North American standard may not seem like much, the real stabilization of the cells happens as the lumber is brought down below 8%.

I make this point specifically, because a lot of lumber will immediately start to pick up moisture when it comes out of the kilns. In our region on the east coast, 10-12% can be the equilibrium moisture content, so kiln drying to 6-8% may seem unnecessary. But it is the setting of the cell walls that is the important part of the drying process. Once the wood is baked appropriately, it will pick up moisture slower and shed it quicker, which means dramatic movement (warping, twisting, bowing) won’t happen as much when a rain storm blows into town for a few days and moves on. So while the humidity levels may skyrocket for a few days, it is unlikely that the wood in your trim, floor, walls, etc. will climb quite as high. More importantly, when the percentage does climb, it does so slowly, preventing cracks in the wood or other damage from a quick change. For more details on kiln drying, we have another article that you might enjoy.

The Bottom Line

- Quality: you want a product that will be durable and not crack up and warp out of shape as it moves from lumber yard to job site – and then for years down the road as seasons change.

- Price: extra drying takes time and money, and so lumber properly dried for this region will inevitably cost more. This is extremely important, because whether it has been re-dried or not, it can all honestly be called “kiln dried”.

As many large brokers and conglomerates start to introduce African hardwoods to the market on a large scale, we begin to see price variances that many yards struggle to match. In general, when major price differences occur from one supplier to another, some step in the quality control process was skipped, and you have to be certain that you are getting the right product.

In other words, ask your supplier if the lumber has been re-dried to North American standards. If you are feeling really daring, ask them about their drying process and their quality control, so that you can be sure you are really getting the product you want.

Really informative and useful , many Thanks for passing on your experience and knowledge

Thanks for your article. I am just about to try the Utile for millwork. I now have the info to ask the rigjt questions.

Thank you Shannon for such a thorough insite to the complexity of wood. Whenever I’ve tried explaning the idea that wood is hydoscopic, people look at me like I’ve got two heads! You make me feel better. Keep it up.